Funerary monument of Pope Alexander VII, meaning the triumph of virtue over death

Tombstone monument of Pope Alexander VII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, fragment, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Allegories of the virtues, tombstone of Pope Alexander VII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Tombstone monument of Pope Alexander VII, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Allegory of Charity, tombstone monument of Pope Alexander VII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, fragment, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Tombstone monument of Pope Alexander VII, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, fragment, Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano

Pope Alexander VII during the procession of Corpus Dei, Giovanni Maria Morandi, Nancy, Musee des Beaux-Arts

A year after assuming St. Peter’s throne (1655), Pope Alexander VII called upon his trusted artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini and entrusted him with creating his funerary monument. However, the commission was not completed for another two decades, after the pope’s death. As it would turn out, Bernini created a masterpiece which would forever be remembered in the history of Baroque sculpture and still today has lost none of its charm.

A year after assuming St. Peter’s throne (1655), Pope Alexander VII called upon his trusted artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini and entrusted him with creating his funerary monument. However, the commission was not completed for another two decades, after the pope’s death. As it would turn out, Bernini created a masterpiece which would forever be remembered in the history of Baroque sculpture and still today has lost none of its charm.

The nagging thoughts of his death, which had convinced the pope to rapidly commission for the completion of his funerary monument, subsided over time. During his twelve-year-long pontificate, Alexander VII became so involved in numerous undertakings and foundations, that the funerary monument was put off to the side. Therefore, when he died (1667), he was “provisionally” buried in the Vatican Basilica, while his heart was laid to rest in the Chigi Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo. It was there, that he desired to be buried as cardinal, prior to becoming pope, in the company of his ancestors and the representatives of the Chigi family. Ultimately the pope’s funerary monument was unveiled in 1678 in the left nave of the Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano.

What can we see in this oft-praised funerary monument? A pope triumphant over death, a man who found an effective antidote against the fear of death in the shape of a pious and modest life. Let us recall that one of the first works completed by Bernini at the commission of the new pope, was a marble skull, which would remind the pontifex, of the futility of human life, everywhere he went. We also know that a coffin was made ready in the case of the pope dying.

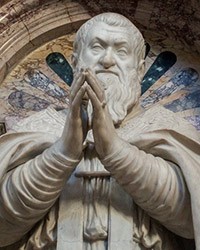

Let us take a closer look at the individual elements of the monument. Bernini set the pope’s figure on a high plinth and depicted him in a kneeling position. We can already see such a presentation in the monuments of Popes Sixtus V and Paul V in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, however, in the Vatican Basilica, this was an absolute novelty. The popes incarnated in marble and travertine lay or sat (enthroned), but they did not kneel. The choice of such a position did have its justification. Pope Alexander VII was a man, who was not only consumed by thoughts of his own death but also devoted to penance. One of its manifestations was the initiation of the procession of Corpus Christi while kneeling. We can only imagine, that for the elder Alexander, moving through the narrow streets of the Borgo on his knees was no easy feat. That is why during the procession he was actually carried by eight men on a special platform. But he did kneel, holding a monstrance placed on a prayer desk. This unusual act of religious emphasis aroused general interest of not only the Roman populace but also of the monument's designer.

Bernini placed the kneeling, immersed in prayer pope in a deep niche, which, however, had one flaw in the shape of a door found in it. What would otherwise be viewed as an obstacle, was used by the ingenious artist to create a significant element. Behind this door, he hid Death, which rears its head for a moment and shaking an hourglass calls upon its servant – the pope. In order to “embellish” this Death, while at the same time camouflage the entrance, Bernini covered both the door and the skeleton (symbolizing death) with a heavy curtain. This trick, often used in the later creations of this sculptor, worked wonders. The curtain created out of travertine and jasper, imitated a pall, which was at that time used to cover a coffin, provides volume, dynamics, and pompousness to the entire composition, while also allowing the viewer to forget about the lack of a sarcophagus, which was at that time an integral part of a papal funerary monument. Death, emerging from behind the pall, whose face we cannot see, but only feel the real roundness of its skull, does not fill us with any great fear, while the clumsiness it exhibits in struggling with the fabric, even causes us to stifle a laugh. This idea is a show of the genius of Bernini – evidence that comedy and tragedy can coexist even in such a deadly serious subject.

However, that is not all, which the artist had prepared for us, but only a prelude of that what is found at the base of the plinth. It is flanked by allegories of Virtues. Those found in the first row are Truth (on the right) leaning with her foot on the globe in the very spot where England and Sweden are located and Mercy with a child in her arms. In the back, due to a lack of space, there are only partially visible figures of Justice (in a helmet) and Foresightedness. All these figures directly refer to the character and the pontificate of Alexander VII – a just and wise pope, who valued truth and exhibited mercy.

And now let us close our eyes and imagine a completely nude figure of Truth and the uncovered arms and bosom of Mercy – for that is how they were presented by Bernini. Unfortunately, their nudity was so intolerable for the next pope, Innocent XI, that he had them covered with robes made of bronze and that is how we seem them today. We can only assume that this was appreciated neither by the artist nor by Flavio Chigi – the cardinal-nepot of the deceased pope, who supervised work over the monument of his uncle and was known for his love of the beauty of a woman’s body.